The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania committed to provide free breakfasts to all of its schoolchildren during the 2022-2023 school year. Statewide, about 800,000 children became newly eligible for breakfast at no cost, on top of the 900,000 who were already traditionally certified. This means a total of 1.7 million school-aged children are eligible for free breakfast in Pennsylvania.

Expanded access to free breakfasts is a well-targeted and effective policy. In Pennsylvania, children are 80% more likely to be food insecure than adults, according to Feeding America’s 2022 Map the Meal Gap report.

- As of 2020, there were about 436,000 food insecure children under the age of 18 in the Commonwealth. Expanding school breakfasts will direct at least $21.5 million of additional funding to Pennsylvania’s public schools and could help leverag

e additional federal resources.

e additional federal resources. - Across the 27 counties that comprise the Central Pennsylvania Food Bank’s service territory, there are about 225,000 public school children who may now receive free breakfast in addition to the 174,000 students who were already eligible.

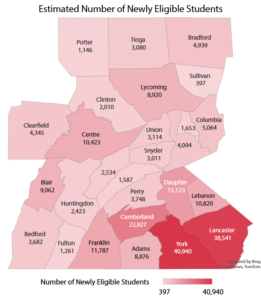

York County has the most newly eligible children of any CPFB county, at nearly 41,000 students, followed by Lancaster (about 38,500 students), Cumberland (nearly 23,000 students), and Dauphin (about 15,000 students).

In general, the most populous counties had the greatest increase of eligible students, but some counties, such as Lancaster, already had a substantial proportion of students eligible for free breakfast due to some districts’ or schools’ use of the federal Community Eligibility Provision (CEP). CEP allows schools in high-need areas to provide breakfasts and lunches to all students at no charge and without any paperwork requirements.

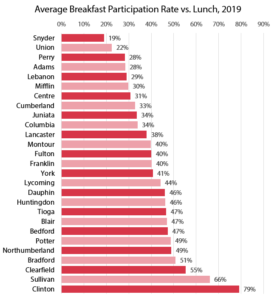

Increased eligibility does not automatically result in increased or universal participation in school breakfast. Central Pennsylvania schools that already had universal eligibility through CEP only had a 61% average participation rate in 2019.

Participation rates may be lower than expected in CEP school districts due to time-based access barriers; even when breakfast is free to all students, if it is only served before school starts, students may not arrive in time to eat due to tight schedules or transportation delays. Alternative breakfast models, such as breakfast in the classroom for elementary schoolers and grab-and-go or second-chance breakfast in secondary schools, can help increase student access to breakfast and therefore participation rates in situations like these, though it is important to note that school districts may also face staffing challenges that make offering breakfast for a longer time or via an alternative model difficult.

Across all public schools in CPFB counties, the average breakfast participation rate in 2019 was 40%. Clinton County had by far the highest participation rate at 79%, nearly twice the average; Snyder was lowest and just slightly below half the regional average at only 19%.

If participation remains flat from 2019, the additional revenue generated for central Pennsylvania’s public schools by this eligibility expansion can be estimated at $7.2 million for the 2022-2023 school year. Of the CPFB’s counties, York County can receive the most additional revenue, at about $1.2 million, followed by Lancaster at $783,000, Dauphin at $508,000, and Cumberland at $445,000.

School breakfasts help students focus on their schoolwork, and school breakfasts leverage existing underutilized federal funding.

About 16.5% of Pennsylvania’s children were food insecure in 2020, and about 18% of these children lived in households that were above the income thresholds for free or reduced-price meals (Feeding America). Access to school breakfast allows food insecure families faced with high inflation to stretch their food budgets further whether they previously qualified for free breakfast or not. The universality of the program also saves children from the stigma about who is eating breakfast at school and why. However, stakeholders must act to help as many children as possible with free breakfasts.

- Until the program ends, school districts are encouraged to use the additional funds to implement alternative breakfast models that maximize the impact of the current expansion.

- Alternative breakfast service models, such as breakfast in the classroom in elementary schools and grab-and-go or second chance breakfast in secondary schools, are proven to increase school breakfast participation.

- Community stakeholders should work with schools, particularly those that qualify for universal free breakfasts under the federal Community Eligibility Provision (CEP), to implement alternative breakfast models.

- Many CEP school districts in the CPFB’s service territory have below-average participation rates and are not taking full advantage of federal funding opportunities to help children.

- These schools are also located in areas that have the highest child poverty and child food insecurity rates in the CPFB’s service territory.

- In advocacy and policy work, anti-hunger advocates should encourage state policymakers to make universal free meals permanent in Pennsylvania.

- The one-year expansion of breakfast eligibility presents an enormous opportunity to build support for making the program permanent, or even to make all school meals free to all students in perpetuity, as Maine and California have done. Legislation was introduced last session in the Pennsylvania General Assembly that would make school meals free for all students, permanently.

- The impact of the single-year breakfast expansion and the success of the COVID-19 waivers and programs in other states provide compelling evidence of how universal meal programs can work.

School meals provide in-kind support to food insecure children in a setting in which they are already comfortable. Like SNAP, school meals are convenient and effective for families. By supporting school meal expansion, anti-hunger advocates can help ensure that every child has the nutrition needed to focus and learn effectively.

You can download the full brief here