When we talk about history, we’re really talking about someone’s description of historical events–a story. The accuracy of our stories depends largely on first-person accounts by people who were there. Written accounts of history by people who were “in the room where it happened” are common, especially in American history. We celebrate the words and actions of American heroes in history books, movies, art, popular culture, and our nation’s shared memories. But we don’t always get the story exactly right.

The Juneteenth holiday is such a story. If you’ve heard of Juneteenth, you might know that it’s a day celebrated by African Americans since 1865. The story goes something like this…The Civil War was fought between the Northern Union Army and Southern Confederate States unwilling to abolish the horrific practice of buying and selling human beings as property. Along came Abraham Lincoln whose deeply held convictions led him to end the “peculiar institution” that kept nearly 4 million African people enslaved. As for Lincoln’s motivation, we’re told it was his compassionate view that Black people deserved to be free in the land of liberty. The Civil War was fought to free the enslaved people providing free labor to an increasingly wealthy, white, southern, agricultural society, right?

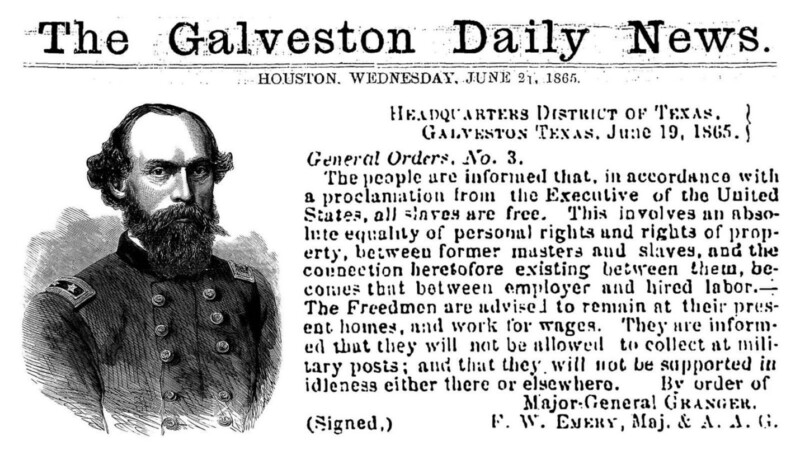

With the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, enslaved Africans were free to leave their captors and pursue an American dream that was never intended for them. So, you might imagine that the story of enslaved people in Galveston, Texas learning about their new freedom more than two years after the proclamation is a compelling story. History tells us that Union General Gordon Granger rode into Galveston on June 19, 1865, and read General Order Number 3 to Galveston’s uninformed slave population. The order reads as follows:

“The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired laborer.”

By June 19, 1865, two years had passed since President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, almost five months since Congress passed the 13th Amendment, and more than two months since General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Confederate army at Appomattox Court House. So why did Granger need to act to end slavery?

The reality of Galveston’s delayed emancipation wasn’t due to a lack of news, it was the sheer force of armed Texas Confederates and their refusal to abide by the new law of the land, that people remained enslaved. “During the Civil War, white planters forcibly moved tens of thousands of slaves to Texas, hoping to keep them in bondage and away from the U.S. Army. Confederate Texans dreamed of sustaining the rebel cause there. Only on June 2, 1865, after the state’s rebel governor had already fled to Mexico, did Confederate Lieutenant General Edmund Kirby Smith agree to surrender the state of Texas.

After General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox in 1865, the Union Army found the confidence to show up on the barrier island of Galveston with 1,800 troops to take on the rogue state’s confederate holdouts resisting the new order. “Within weeks, fifty thousand U.S. troops flooded into the state in a late-arriving occupation. These soldiers were needed because planters would not give up on slavery. In October 1865, months after the June orders, white Texans in some regions ‘still claim and control [slaves] as property, and in two or three instances recently bought and sold them,’ according to one report.”

And not only were Texas slave-holders aware of the delayed emancipation but most enslaved people knew it too. The idea that these people learned of their freedom only when Granger showed up is a historical inaccuracy. Felix Haywood was an enslaved man in Texas during the Civil War. He was quoted as saying, “We knowed what was goin’ on in [the war] all the time,” At emancipation, “We all felt like heroes, and nobody had made us that way but ourselves.”

The image of General Granger riding into Galveston and reading General Order Number 3 to jubilant enslaved people is only partly true. He did read the order at five locations in Galveston: At the 1861 Customs House, the Osterman Building, the Court House, Ashton Villa, and Reedy Chapel at the Galveston AME Church. But his audience was the resistant slave owners, not enslaved people.

The power of his words was eventually backed up by 50,000-armed Union soldiers in Galveston. June 19, 1865 was the beginning of a celebratory tradition we now know as Juneteenth or “Freedom Day”. President Biden declared Juneteenth a national holiday in 2021. Juneteenth celebrations around the country include rodeos, fishing, barbecuing and baseball as well as many of the traditional foods still seen at celebrations today. Strawberry soda and other red food items are still popular selections at Juneteenth events. The color is said to represent the spilled blood of Africans in America. There is even a Juneteenth flag. As Americans continue to grapple with our country’s oppressive past, we also celebrate the progress made by facing aspects of our difficult history head on.

The Central PA Food Bank’s ongoing commitment to EDIB (equity, diversity, inclusion and belonging) and social justice pays tribute to the resiliency of enslaved Africans and their descendants who continue to contribute to America’s maturity as the world’s leading democracy. Together, we strive to create a more perfect union knowing that change begins with each one of us as individuals. While America’s true history may cause anxiety for some, ignoring mistakes of the past will only serve to drive us further apart. Juneteenth reminds us of a troubling past but also celebrates the very best of American’s commitment to a brighter, more inclusive future where our founding documents and the promises they make are more available and real to every American. Visit Juneteenth.com for more information and additional resources.

Written By:

Joe Morales Former Director of Equity, Central Pennsylvania Food Bank